Key Takeaways: Read Books like Venture Deals. Think from First Principles. Gather Market Intelligence.

Everyone Starts Off as a Greenhorn

Over the years, I have taken my fair share of lumps in negotiating venture deals. Venture law is not something you pick-up overnight. It requires multiple disciplines. It takes years of practice. And it requires you to constantly stretch yourself to learn.

In 2008, after passing the California State Bar and entering the worst labor market since my great-grandparents made it out of the Dust Bowl, no one wanted to hire a fresh-faced startup lawyer. Instead, they wanted a scrappy litigation associate. So, that’s what I became. But litigation wore thin on me. And so, in 2014, I packed up my things and headed up the coast from San Diego to Los Angeles to hang my own shingle and start working with entrepreneurs.

In 2016, I read a story by Fred Wilson about the first time he broke into VC:

I remember the first week of my career as a VC. I was 25 years old, it was 1986, and I had just landed a summer job in a venture capital firm. One of the VC partners, Bliss McCrum, peeked his head into my office and said to me, “Can you model out a financing for XYZ Company at a $9 million pre-money, raising $3 million, with an unissued option pool of 10%?”

I sat at my desk and started thinking about the request. I understood the ‘raising $3 million’ bit. I thought I could figure out the ‘unissued option pool of 10%’ bit. But what the hell was ‘pre-money’? I had never heard that term. This was almost a decade before Netscape and Internet search so searching online for it wasn’t an option. After spending ten minutes getting up the courage, I walked back to that big office, peeked my head in, and said to Bliss, ‘Can you explain pre-money to me?’

—Foreword, Venture Deals

It reminded me of the first time a client asked me to model their pro forma cap table. Man—I thought, ”what’s a cap table?” At least I had Google.

Venture Starts with 📚

Before you learn how to model a cap table, structure a venture deal or draft a term sheet, you might want to read about it first.

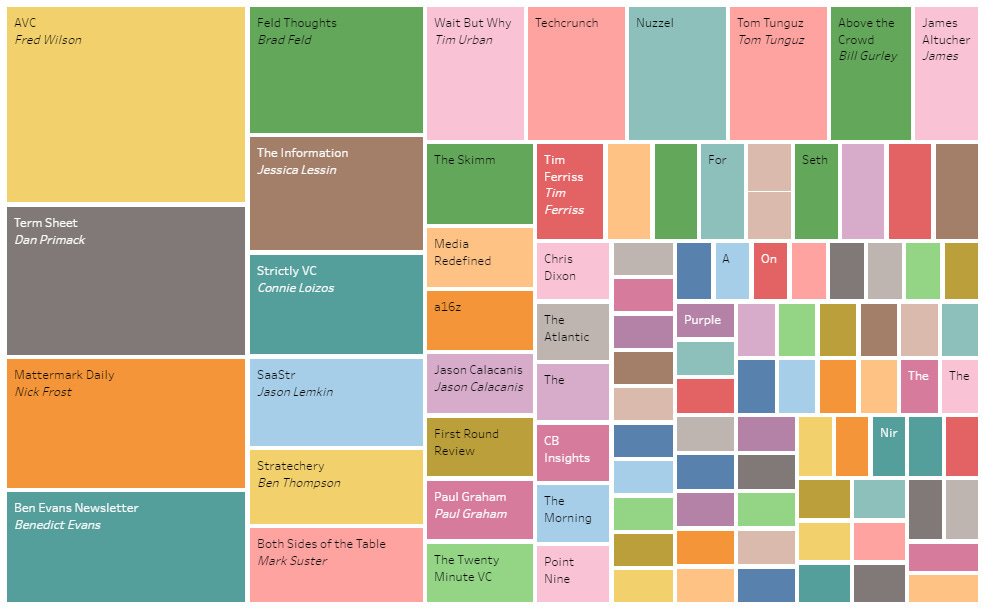

In 2016, this is what the “best venture capitalists in the world read each morning”:

Today, these authors are still publishing high quality VC content, often for free.

Strong Opinions, Weakly Held

I enjoy reading materials from other lawyers like José Ancer and Joe Wallin. José runs an insightful blog at Silicon Hills Lawyer, which is founder-focused. He’s also a co-author of the The Holloway Guide to Raising Venture Capital and The Holloway Guide to Equity Compensation. Joe blogs at The Law of Startups and is also a co-author of The Holloway Guide to Raising Venture Capital and The Holloway Guide to Angel Investing. Both authors offer fresh perspectives and, at times, strong opinions. I like that. It helps me explore my own biases and values even if I disagree with them.

For example, what’s the ideal length of a term sheet?

Joe’s answer from the Holloway Guide:

“Term sheets should be short (1-2 pages), easy to understand, and free of legalese—save perhaps a sentence about the non-binding nature of the proposal.”

José’s answer from SHL:

“Inexperienced founders are often led to believe that the shorter/simpler the term sheet, the better. This is categorically wrong.”

So, which one is correct—a short term sheet or a long one? It depends on the context. The best term sheets are the ones that close the deal.

Fred Destin nailed it:

“A good term-sheet is an unqualified term-sheet.”

Read Books

Books provide a great foundation for thinking clearly and uncovering new truths.

You could try to pound your head against the wall and think of original ideas or you can cheat by reading them in books.

Starting out, I read legal hornbooks like Business Transactions by Alan Gutterman and Structuring Venture Capital, Private Equity, and Entrepreneurial Transactions by Jack Levin, Donald Rocap and the late Prof. Martin Ginsburg. These books are excellent resources for lawyers and professionals, but probably too heavy for most fund managers.

More VC-friendly books have been published recently—ones like the insightful Secrets of Sand Hill Road by Scott Kupor, managing director at @a16z. Holloway also offers some great content in its Holloway Guide series on topics such as angel investing, startup equity compensation and raising venture capital.

But one book is universally recognized as the #1 resource in venture capital—the book that Mark Suster wrote “every entrepreneur and VC should own”. Venture Deals: Be Smarter Than Your Lawyer and Venture Capitalist, by Brad Feld and Jason Mendelson.

Venture Deals was originally published in 2011. The current version is in its 4th Edition (2019). There are a lot of reasons why this book has withstood the test of time:

At 270 pages, it’s easy-to-read, but compressed

The body of work comes from decades of blogs, classes, negotiations & articles

Brad Feld is an advocate of startup communities for 30+ years

Co-author Jason Mendelson is a former Cooley lawyer

Kauffman Fellows & Techstars host a free online course with Brad & Jason*

*Venture Deals Online Course goes live on September 13, 2020 – November 6, 2020 (10,000+ registrants and 2,000+ people completed it during summer 2020).

Thinking from First Principles

Books are great, of course, but as Bill Walsh said:

“Persistence is key as knowledge is rarely imparted on the first attempt.”

In good times, when speed and efficiency are competitive advantages, context tends to get lost in the high resolution financing documents of Safes and Series Seed Notes. Terms become distilled down to a few basic ones, like caps, discounts & pro rata rights. Lawyers become discouraged from editing anything but the most core economic terms. The trend line for startup equity growth over the last 10+ years has been up and to the right. So why worry about the downsides or legal protections?

The opposite is true in bad times. Without knowing it, emerging fund managers have set themselves up for bad habits. According to AngelList, 80% of early-stage financings use Safes rather than convertible notes. And at the Seed stage, a Safe is considered a favorable alternative to a priced round. Over the past year, I have seen some signs of bad habits emerging from all sides:

Several Safe rounds stacked with different valuation caps & discounts.

Safes with $175M+ valuation caps, no discount, early-stage.

Heavily-modified Safes clearly favoring one party.

Ignoring the downside risks of Safes and notes compared to Preferred Stock.

If you read this newsletter, you know that nothing is standard in venture capital. True wisdom is earned from experience. Books and blogs are a great way to uncover original ideas and lay the foundation, but unless you have a good mental model of the profession, you won’t know what you’re up against or what to look out for.

Model Term Sheets

If a fundamental breakdown between the parties is to happen, it almost always manifests itself in the term sheet negotiations.

A quick primer on term sheets:

A term sheet is a basic outline of the key terms of a venture deal.

The term sheet is critical. It sets the stage for the final deal structure. Don’t think of it as a letter of intent. Think of it as a blueprint for your future relationship.

Unlike a typical M&A term sheet, you have to work with your negotiating partner after the deal closes. “Negotiation is relationship building.”

A shorter term sheet usually favors investors but often misses important details.

Context is key:

Are the parties familiar with the structure of the proposed deal?

Do they operate in the same or similar sector, stage and geography?

Are your lawyers and their lawyers familiar with the process and terms?

What are the three most important deal points for you? To your negotiating partner? What are their real concerns and motivations?

There is no shortage of term sheet forms, articles and generators floating around the Internet today. So perhaps the worst advice anyone can give you is to “go download a standard term sheet generator.” Where do you start? How do you know which terms are important? What’s market? This article answers some of those questions.

1. Term Sheet Forms, Articles and Generators

Here are the best resources on term sheet forms, articles and generators:

Forms + Generators:

Enhanced NVCA Model Term Sheet (Aumni + NVCA, August 2020)

Series Seed.com (Cooley) Term Sheet + Equity Financing Package

Y-Combinator Series A Term Sheet (but see caution from SHL here)

Articles:

“Term Sheet Essentials” in The Holloway Guide to Raising Venture Capital.

“Negotiating Term Sheets: Focus on What’s Important” by CooleyGo.com

“The Option Pool Shuffle” by Navi in Venture Hacks

“The Three Terms You Must Have in a Venture Investment” by Fred Wilson

“How VCs calculate Valuation Differently” by Mark Suster

2. What are the Most Important Terms?

Everyone thinks valuation is the most important term, but as a wise person once said:

“Tell me your price and I’ll tell you my terms.”

Valuations matter only in the context of the offering. They have far less significance than other economic terms like dilution, liquidation preferences or pro rata rights.

Brad Feld has found only two essential terms matter in any venture capital deal: Economics and control. I put together a quick list on Twitter:

3. What’s Market?

Aumni is the best analytics platform for market terms for venture capital deals. They have partnered with the NVCA to analyze over 35,000 transactions with 17,000 unique investors spanning a decade. Some of the data were pretty revealing even to me. We’ll go over only a few insights here, but there are several dozen more that can be found by downloading the free form at the end of this article.

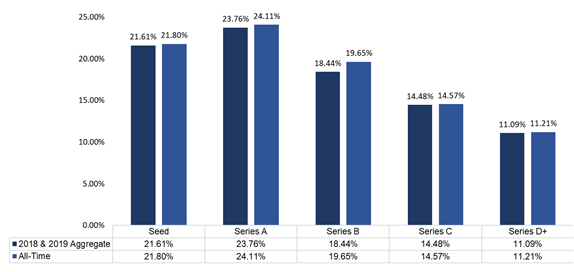

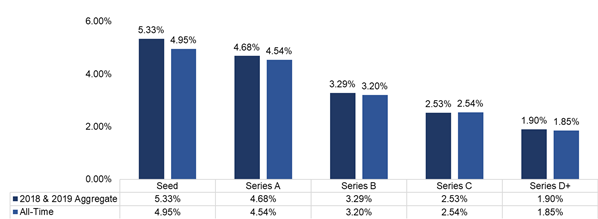

Dilution—Across All Investors in a Round

This chart represents the median percentage of fully diluted ownership that the new money class purchases in an equity financing across the stages listed above.

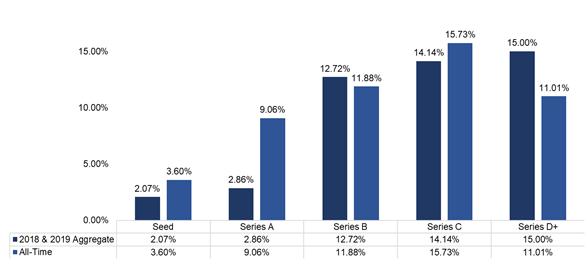

Dilution—Lead Investor (often, lead investors will take ~55%+ of the round)

This chart represents the average percentage of fully diluted ownership that the lead investor purchases in an equity financing across the stages listed above.

Deviation from 1x Liquidation Preference Multiplier (% that don’t have 1x)

This chart represents how often various equity classes have any liquidation preference multiplier other than 1x.

Participating Preferred (% of deals that have it)

This chart represents how often participating preferred stock is outstanding for companies across stages.

Pay-to-Play (% of deals that have it)

Frequency of Redemption Rights Across Stages

Average Major Investor Threshold as a % of Fully Diluted Ownership

% of Equity Financings with Employee Vesting Protocol Covenant

This chart represents how often the employee vesting protocol covenant is present across stages.

Investor Counsel Fee Cap Across Stage

Subscribing to the Law of VC newsletter is free and simple. 🙌

If you've already subscribed, thank you so much—I appreciate it! 🙏

As always, if you'd like to drop me a note, you can email me at chris@harveyesq.com, reach me at my law firm’s website or find me on Twitter at @chrisharveyesq.

Thanks,

Chris Harvey