#26 Episode - The Three-Body Problem in VC

The U.S. Venture Industry has $300B of dry powder, but there's just one problem

Key Takeaways: The incentives of the three key players in venture capital are diverging, $500B in unrealized gains are at risk of being marked down in the coming years, venture deal terms are starting to look less founder friendly, and three practical tips for venture capital managers to stabilize their operations.

The Three-Body Problem has vexed scientists for over 300 years after it was first discovered by Isaac Newton. The problem describes the odd result of what happens when two orbital objects in space, such as the Earth and the Moon, interact with the gravitational pull of a third celestial body, such as the Sun.

While the motion of two objects is predictable and follows a linear path, the introduction of a third body results in random, unpredictable and unstable motion. No math equation can solve for it. Not even Einstein’s General Relativity.1

Author Liu Cixin popularized the Three-Body Problem in his science fiction novel published under the same name. In the novel, the problem is described as follows:

“The three-body system is a chaotic system, one in which tiny perturbations can be endlessly amplified. Its patterns of movement essentially cannot be mathematically predicted.”2

The Three-Body Problem in Venture Capital3

As applied to venture capital, the Three-Body Problem refers to the industry’s three key players and the cost of capital as the driving force influencing market behavior:

1—Founders are seeking funding before capital dries up

2—VCs are sitting on a $300B powder keg, hesitant to draw down capital

3—LPs want to preserve their cash to invest in high-yield assets with less risk

In 2023, with interest rates going up, incentives are diverging:

Venture Fund Metrics

Over the last decade, a record amount of venture capital has been raised and deployed:

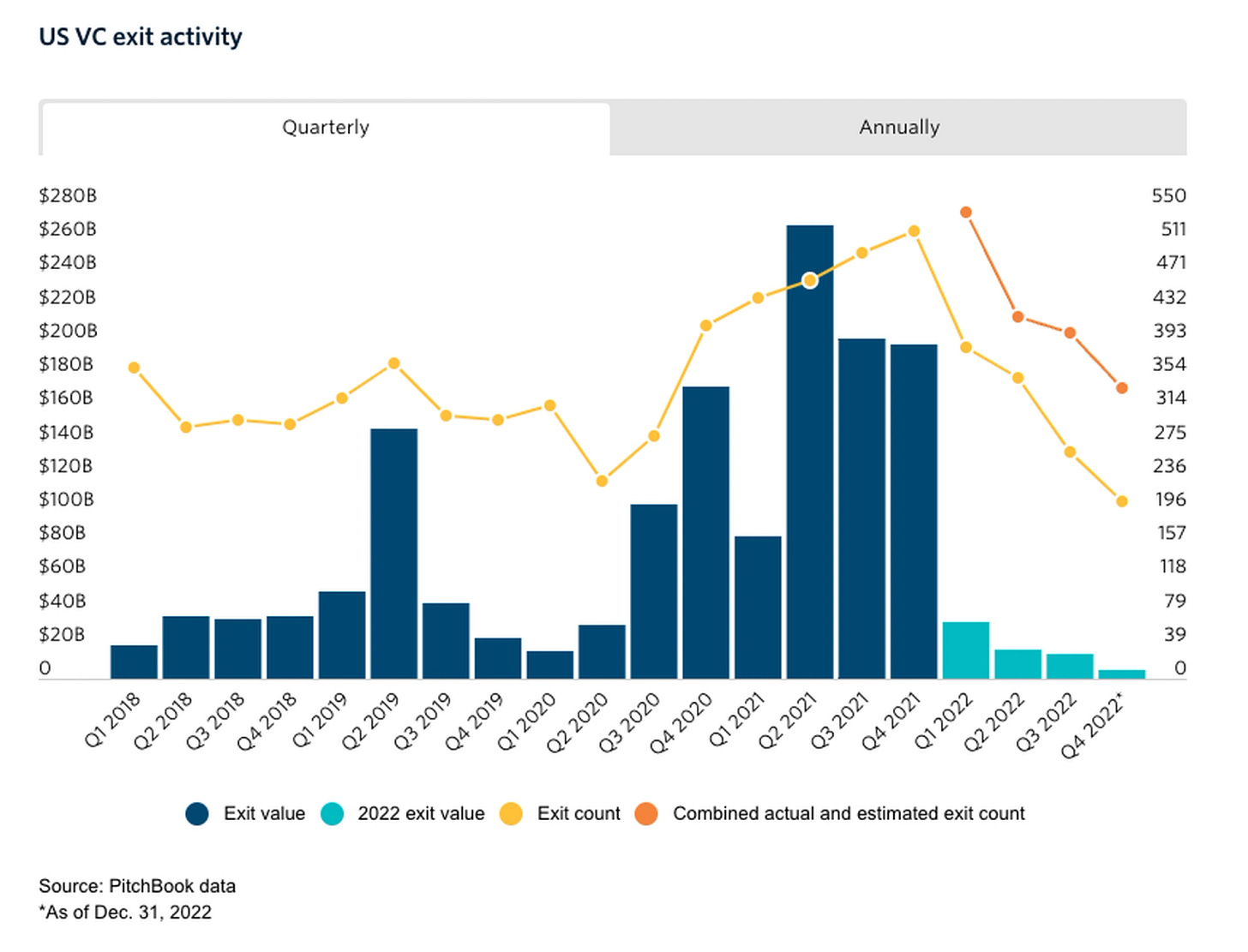

In 2021, there was a record-breaking 18,521 US venture deals, which was 39% higher compared to 2020.4 The total deal value reached an unparalleled amount of $344.7 billion, showing a year-over-year increase of 101%. Moreover, VC-backed exit values surged to an extraordinary $753 billion, an increase of 131% YoY. Times were good for venture capitalists during rock-bottom interest rates.

But by the end of 2022, as markets faltered and interest rates crept up, deal volume slowed down and exits all but dried up.

In 2023, the amount of dry powder—or venture capital raised but not deployed—has accumulated to about $300 billion in the U.S. This abundance of capital comes at a time when M&A exits and public listings have been heavily slashed.

Venture portfolio valuations have not adjusted. VCs are still riding the wave of mostly unrealized gains (TVPI)—while realized returns (DPI) have been left wanting.

This graph shows another angle of the hidden risks in the top 25% of VC portfolios:

There are three main takeaways:5

The orange horizonal line is the average return of the top 25% of VCs taken from 1997 through 2017.6 In other words, ~2x DPI is the average return of top quartile funds.

The gray vertical bar (TVPI) indicates the markups of the top quartile’s portfolios. The blue bar (DPI) represents the actual returns. In simple terms, gray bars are mostly paper markups in the early years and blue bars are the actual returns of the top quartile of VCs from ‘97-’17.

Over time, as TVPI and DPI converge, the gray bars and blue bars eventually become one. For example, despite the 5x TVPI in 2012, LPs have only received 2x their investment (DPI), while the ~3.5x in 1997 is the actual return of capital distributed to LPs in that vintage.

Here’s a more recent look which shows the median return profile of VC portfolios may already be correcting:

Will we see massive markdowns and TVPI corrections, or will the next few years significantly outperform the last 10+ years?

If we believe the next few years will outperform as the last 10+ years, then the vintages starting in the year 2012 represent the largest set of returns in the last 40+ years of venture capital. However, if the markets do not outperform the next few years, the orange line represents a regression to the mean.7

The key takeaway is as follows:

$500B in unrealized gains are at risk of being marked down in the coming years

Historical Lessons from the Dot Com Crash

For founders, a similar situation occurred between 2001 and 2004. After the Dot Com crash, capital was tight, which forced founders to accept more investor-friendly terms such as liquidation preferences greater than 1x, liquidation participation rights, and full ratchets that gave investors full anti-dilutive ownership percentages.

Some investors have described today’s funding environment as an “existential crisis,” urging founders “to buckle up” and prepare for a potential “mass extinction event”:

Some recent data are bearing this out—here’s a graph of liquidation preferences >1x:

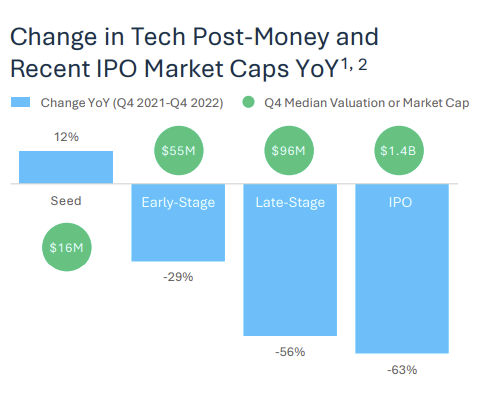

In addition, valuations across all stages are being slashed across the board (Seed stage has fared the best, but it is still down from 2021 valuations):

This comes at a time when cash is tight for startups as runway is dwindling for many and the clock is ticking until the next round—an average of 24+ months (expect a lot of bridge financings in 2023):

While “dry powder” is legally available capital, at the same time, LPs want to preserve cash as interest rates creep up. LPs have an incentive to slow down their capital calls knowing that (a) near risk-free investment returns are increasing, and (b) their investment portfolios are at risk of markdowns.

For VCs, calling capital now is a little like playing a game of Jenga. Making too many capital calls could destabilize the venture capital system, similar to how removing one too many blocks from a Jenga tower can destabilize or lead to its collapse.

Three Practical Tips*

Based on conversations with my fund clients and their limited partners in the past month or so, I have three suggestions* that could potentially stabilize the situation:

Offer LPs co-investment opportunities with carry and fee discounts/waivers.

Adjust management fee schedules by pausing or slowing down capital calls in 2023. Your LP advisory committee (LPAC) should vote to avoid any conflicts of interest.

Consider subscription lines of credit for short-term cash needs,8 but exercise extreme caution when using this strategy—there's no such thing as a free lunch.9

*Not legal advice, speak to your counsel to evaluate your specific situation for risks and other legal considerations.

While the state of the venture capital markets for 2023 is faced with challenges—such as cash preservation and the risk of markdowns—the future looks bright for VC firms. VCs are still sitting on $300B+ in capital commitments and have the opportunity to stabilize the system by offering co-investment opportunities, adjusting fee and capital call schedules, and exercising caution with the use of subscription lines of credit. By taking these practical steps, VCs can navigate the current landscape and continue to drive innovation and growth in the years to come.

Credit to Kyle Harrison and his article "Dreaming Of Dry Powder" for my source of inspiration and whose original ideas I poached from above. Also major hat tips to Juniper Square for their Q1 2023 - State of Venture Capital report in which several graphs from Pitchbook were kindly repurposed, as well as Silicon Valley Bank (SVB), State of the Markets H1 2023.10

See Three-body problem, Wikipedia (2023).

See Liu Cixin, The Three-Body Problem (2006), translated from Chinese to English by Ken Liu (2014).

This concept was first referenced in a presentation by Frank Rotman of QED Investors (“This report gives the framework to the changes that are occurring in the startup ecosystem, the LP community and how VC firms need to strategically reorient themselves to survive”). See Frank Rotman, The Three-Body Problem: Finding the New Stable Points in Venture Capital (2022). Rotman’s analysis focused on the “four stable points for VCs” which concerns the modern archetypes of VC firms, including (1) multi-stage firms that scale, (2) non-consensus alpha chasers, (3) late stage generalists, and (4) solo capitalists.

Here’s the key takeaway:

Eugene Tetlow, Q1 2023: The State of Venture Capital, Juniper Square (Feb. 13, 2023).

Technical terms are defined in more detail in Law of VC #23 Episode:

• TVPI: “Total Value of Paid-in Capital” is calculated by dividing the total value of the fund (including realized & unrealized gains) by the total amount of capital invested in the fund.

• DPI: “Distribution to Paid-In Capital,” the realization multiple for LP returns, which is a measure of the actual cash and other assets distributed to LPs relative to the amount of capital they have invested in a venture capital fund.

On average, a fund takes about 6 years for its performance to be accurately ranked relative to its peer group. “Quartiles” is a statistical term used to compare the performance of different funds in the same “vintage,” or initial fund launch year. Funds are divided into four quartiles adding up to 100% based on their performance relative to other funds in the same vintage. For example, the top 25% of funds from 2017 are in the first quartile, the next 25% in the second quartile, and so on. The point is that it takes some time for a fund’s true performance to become apparent. Early performance in the rankings may not necessarily be a good indicator of long-term success. In other words, funds showing 6x or more TVPI in 2012, while having less than 2x in DPI over 10 years later, is not a good sign that the funds will outperform at that level. Again, the historic average returns of the top 25% of funds from 1997 to 2017 is two times your initial investment (2x DPI).

For readers of The Three-Body Problem, the orange line can act like the Flying Blade, a laser-like weapon that cuts things apart like a hot knife through butter. Any gray bars above the orange line are susceptible to being whacked down. The only thing that would reverse this trend is if the next few years see greater returns than the last 10 years have, on average. That means unless exits and IPOs start to come back, we’re looking at some tough portfolio fund corrections.

Subscription lines of credit, also known as bridge financing, are a type of short-term revolving credit facility that is secured by the uncalled capital commitments made by investors (LPs) to a venture capital fund (GPs). In this arrangement, a lender such as First Republic Bank or Silicon Valley Bank provides a credit line to the fund managers, which can be drawn down as a cash flow management tool to cover things like management fees or to fund portfolio investments. To secure the credit line, the lender or bank is typically granted collateral in the form of capital call rights, which allow them to call on the LP’s capital commitments if the fund is unable to repay the debt. This type of financing is commonly used to bridge the gap between making investments and receiving capital commitments from investors.

Venture funds may use subscription lines of credit but there are legal and business risks. Here are some of the limitations and potential downsides to using these lines of credit:

Potential Loss of VC Exemption: One of the five elements of a “venture capital fund” which qualifies a person as a VC exempt adviser, require limiting loans to no more than 15% of the fund’s aggregate capital contributions and uncalled committed capital. Any borrowing, indebtedness, guarantee or leverage must be for a non-renewable term of no longer than 120 calendar days, with the exception of a guarantee by the private fund of a qualifying portfolio company's obligations up to the amount of the fund's investment in that company, which is not subject to the 120-day limit. See Section 203(l)-1 (17 CFR § 275.203(l)-1) under the Advisers Act of 1940.

Increased risk of default: Using subscription lines of credit increases the overall debt burden of the venture fund, which can limit the fund’s ability to invest in new opportunities and pay out returns to investors. The fund’s LPA has to be amended or allow for such subscriptions and this forces the LPs into a “guarantor” position.

Potential conflicts of interest: If the venture fund is using a subscription line of credit from a financial institution like a bank, the lender may have a different set of interests than the fund’s investors. While it might be fine to wait a year or so to call capital down from LPs, if the bank is on a repayment schedule that’s missed, there will less tolerance for default. This can create conflicts of interest and lead to suboptimal decision-making by the fund managers.

Loss of transparency: Subscription lines of credit can make it more difficult for investors to accurately track the performance of the fund, since the debt and interest payments associated with the credit lines may not be fully disclosed in the fund's financial statements and in the internal rate of return (IRR) of the fund’s performance. The Institutional Limited Partner Association (ILPA) has a recommended framework for accepting subscription lines of credit. See ILPA 2020 Guidance - Enhancing Transparency Around Subscription Lines of Credit, see also 2017 Guidance - Subscription Lines of Credit and Alignment of Interests.

See Silicon Valley Bank, State of the Markets H1 2023.

“2X DPI is the avg for top-quartile VCs...”

yep.