#21 Episode - Everything is a Security

Why Securities Matter, What Securities Are, and The SEC vs. The Crypto Industry

Welcome back. Last time we discussed the three laws that govern 80% of venture capital fund law:

The Securities Act of 1933

The Investment Company Act

The Investment Advisers Act

We visualized and explained that legal framework here:

Today, we are focusing on the core element that ties everything together—securities.

Why Do Securities Matter?

First, securities matter because they are regulated:1

Under Section 5 of the Securities Act of 1933, it is “unlawful for any person, directly or indirectly” to use interstate commerce to offer to sell “any security” unless the person has filed a “registration statement” for the security, unless an exemption from registration is available.

In other words, if you offer or issue securities without (1) registering to go public, or (2) relying on an “exemption,” you are in violation of securities laws.2

For example, in 2020, the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) brought an enforcement action against Telegram for selling digital tokens without registering their offering or finding an applicable exemption. The company agreed to return $1.2 billion of investor’s funds plus pay a $18.5 million civil penalty.

Second, securities matter because they create, store and leverage wealth.3

Growing up in the 1980s, I remember watching Lifestyles of the Rich and Famous, a precursor to reality TV shows like MTV Cribs and Keeping up with the Kardashians.

When Lifestyles first aired, inheritance was the primary source of wealth for the most affluent. In 1982, sixty of the top 100 wealthiest people in the United States acquired their fortunes from inheritance. By 2020, that number shrank to less than thirty.4

Inheritance taxes went down a lot during that time, so that was not the root cause. Nor was wealth lost by mismanagement or fewer people inheriting big fortunes.

Instead, a new source of wealth emerged, “self-made”—more like Keeping Up with the Kardashians and HBO's Silicon Valley, less like the inherited class of Lifestyles.

Jeff Bezos and Elon Musk are the world’s wealthiest people because of their corporate holdings. Kim Kardashian is launching a private equity fund while many successful athletes, including Serena Williams, Kevin Durant, and the late Kobe Bryant all invested in or formed venture capital funds. All of these activities involve securities.

Investor and podcast host Jim O'Shaughnessy predicts that within his lifetime we will see a one person company worth a billion dollars. I don’t think that’s possible without issuing or selling securities.5

In short, securites unlock opportunities for wealth.

What Are Securities?

Key Term: A security is an investment in a common enterprise that is made with the expectation of profits from the efforts of others.

The statutory definition of a ‘security’ covers a broad range of financial instruments that go well beyond just stocks, bonds, and notes.6 All venture deals are securities, including:

Safes

Convertible Notes

Preferred Stock (Series A, Series B, etc.)

Securities also include all “investment contracts”. The Howey test determines if something is an investment contract:*7

An investment of money

In a common enterprise

With an expectation of profits

Primarily or substantially from the efforts of others8

In Howey, a real estate developer named William Howey sold orange groves in Florida. Howey gave new property buyers an option to lease back their land to him. Under this arrangement, Howey would manage their land, cultivate the trees and bring oranges to market for a profit. Essentially, buyers weren’t buying land as much as they were investing in an orange growing business.

The U.S. Supreme Court ruled in 1946 that Howey’s arrangements satisfied the definition of “investment contracts” and therefore should be regulated as securities.

Why? Let’s review the Howey test first:

Nick Grossman, USV partner, made a great visual representation of the Howey test:9

The four elements of the Howey test, briefly examined:

1. Investment of “Money”

The first part of the Howey test requires an investment of “money,” but it’s more than just cash. Money is legal consideration which can take the form of services or even minimal efforts such as information disclosure from user signups.

Remove the “investment of money” and a transaction looks more like a gift or a loyalty benefit, such as Uber credits, airline miles, or credit card points.

2. Common Enterprise

Courts generally analyze a “common enterprise” as a distinct element of an investment contract, but in evaluating digital assets, the SEC finds that a common enterprise typically exists in every transaction.

3. Expectation of Profits*

Without an expectation of profit, there is no investment contract.

For example, the Green Bay Packers have sold millions of dollars of no-dividend ‘shares’ to raise funds over the years without triggering securities laws. How?

For the sixth time in franchise history, the NFL Packers are offering shares of the team. They are offering 300,000 shares at $300 apiece—worth $90 million—but the shares have no equity, pay no dividends, come with no ticket rights, and offer nothing more than an invite to an annual shareholders' meeting and limited “voting rights”. As the ESPN story noted, it's basically a worthless piece of paper.

“It’s basically a worthless piece of paper” sounds like a horrible investment, but that’s exactly why the Packer’s ‘shares’ are not securities. Fans are buying these instruments as gifts to a charitable organization. If the NFL team sells, 100% of the proceeds will go to charity. People complain that the Packers should just ask for donations, but if the stated goal is to buy from a non-profit entity without any chance of ever returning a profit or a return, isn’t that the same thing? Plus, Packers fans may prefer the label of “owner” rather than “NFL team donor”.

4. From the Efforts of Third Parties*

Funds with first party capital. Renaissance’s Medallion Fund, Homebrew Capital (in 2022), and family offices that control their own funds will generally not be offering interests in the fund to outsiders and therefore no securities are found.

Investment clubs. An investment club is a group of select people who pool their capital and make decisions together. If every member in a club actively participates, invests their own funds then the interests in the club would should not be considered securities. However, if the club is over 100 people, or has even one passive member, it may be issuing securities.

Carried interest and GP capital interests in venture capital firms. The general partners of a venture capital firm issue and receive carried interest, which is not third party efforts. The GP's capital interests are also not considered securities because of the first-party nature of managing venture capital firms.

Conclusion

So an investment is not a security without other people’s efforts and a profit motive—follow the money and see who expects a profit. In other words, the focus should not be on asset itself but on the context of the “contract, transaction or scheme” with the expectation of profits and the efforts of other people.

In Howey, it was not the oranges or land sale that made the arrangement a security, but the cultivation of oranges by third parties and expectation of profit that made it so

Speculative Investments That Are Not Securities

What About Investments like Fine Art, Land, Commodities or even NFTs?

It can be hard to differentiate why some investments are securities while others aren’t.

Masterworks is a Regulation A+ crowdfunding platform that buys and sells fine art. Under new crowdfunding rules, the company raises funds using SPVs to acquire art.

If you purchase the art directly from the artist or an art dealer, the artwork is not a security. But if you purchase an interest in an SPV which then buys the artwork, the transaction is a securities purchase.

Put differently, non-security assets wrapped in investment contracts are securities.

ARTWORK IS NOT A SECURITY:

BUT ART WRAPPED IN INVESTMENT CONTRACTS ARE SECURITIES:

What if you and your friends pool your resources together to purchase artwork?

This will depend on the applicable laws and the facts and circumstances, but in general, assuming you and your friends (a) invest your own capital, (b) have meaningful control and management over your investment, and (c) have the ability to make informed decisions, the interests in the work should not be securities. This is like a general partnership model rather than the limited partnership arrangement of the Masterworks model.

Why not just pool resources together with 500+ of your closest Twitter friends?

Any investment with a profit expectation, common enterprise and a large group of investors will quickly test the limits of securities laws. Even if investors have voting rights, when you pool hundreds of people into a single organization, even one passive investor is enough to trigger securities laws. In general, these kind of raises tend to be looked at more as limited partnerships than GP models and qualify as securities.10

What about land sales—can property be a security?

Land use was at the heart of Howey. However, it was not the property, the oranges or even the lease that caused the transaction to be considered a security. It was the arrangement of all those things plus the expectation of profit from selling the oranges.

Contrast this from a typical home purchase where property is personally used to live in or personally used to rent without triggering securities laws.11

Is Bitcoin a Security?

No—Bitcoin has inherent properties that make it a commodity. Importantly, unlike Ethereum or many other tokens, there was no ICO or pre-mined coins sold to passive investors or retained for promoters or related insiders.

Of course, there is “virtually limitless scope of human ingenuity … in the creation of countless and variable schemes” for how bitcoin could be used as a security, but generally not for first party use and exchange of bitcoin on the blockchain network.12

Are NFTs Securities?

While NFT stands for “non-fungible token” the name has no actual bearing on the legal analysis. Is the NFT a unique digital collectable or a gaming token that serves as a blockchain certificate of authenticity? Can you sell an undivided interest in the NFT and earn a stream of income by wrapping or staking it? The former situation is more like art or consumptive use while the latter situation sounds similar to the Masterworks artwork investment model, which is potentially an investment contract.

Let’s explore two perspectives to further illustrate the concepts above.

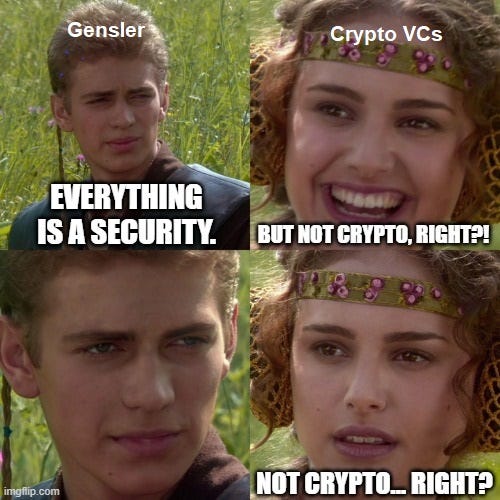

The SEC vs. The Crypto Industry

The Federal Regulator

Gary Gensler, chair of the SEC, knows a security when he sees it:

Gensler's argument is essentially that, besides a handful of digital tokens or coins, every crypto token is fair game for the SEC to regulate:13

“Of the nearly 10,000 tokens in the crypto market, I believe the vast majority are securities. Offers and sales of these thousands of crypto security tokens are covered under the securities laws. … In general, the investing public is buying or selling crypto security tokens because they’re expecting profits derived from the efforts of others in a common enterprise.”

Recently, Gensler shed some light on his everything-is-a-securities theory:

“These are not laundromat tokens. Promoters are marketing, and the investing public is buying most of these tokens, touting or anticipating profits based on the efforts of others.”

To support his position, Gensler has invoked the Common Sense test:14

“When I see a bird that walks like a duck and swims like a duck and quacks like a duck, I call that bird a duck.”

His framework is simple and easy. Essentially, it’s “I know it when I see it”.15

Is this a fair and reasonable position supported by the law?

That depends.

President Franklin Roosevelt once said, “The only thing we have to fear is fear itself,” but it was Senator Joe Kennedy, the SEC’s first chairperson (and JFK’s father) who said:

“No honest business needs to fear the SEC.”

Those who have been under legal scrutiny by the SEC would beg to differ.

Although some people knock Gensler for never attending law school or studying to be a lawyer, he certainly knows what he’s doing. He’s a former Goldman Sachs banker who chaired the Commodities Futures Trading Commission (CFTC). He taught at MIT on this subject and graduated summa cum laude from Wharton with an MBA.

The problem is not a lack of knowledge but that neither Gensler nor anyone else at the SEC are neutral advocates.

Or as Upton Sinclair put it: “it is difficult to get a man to understand something when his salary depends on his not understanding it.”

The Crypto Industry

Meanwhile, crypto insiders, investors and exchanges are crafting their own policy guidelines. They want to prove the opposite point of the SEC: Crypto tokens are rarely, if ever, securities.

Matt Levine wrote about this diametrically opposed viewpoints:

“The crypto industry thinks that literally no cryptocurrencies should be subject to U.S. securities law; U.S. securities regulators think that almost all cryptocurrencies should be subject to U.S. securities law. It’s a big gap!”16

The “big gap” is the gray area between when a crypto token is a security or not. This may end up being a persistent issue in crypto/Web3 because:

“A basic premise of Web3 is that every product is simultaneously an investment opportunity.”17

Or, a more cynical take:

“[The] basic model of Web3 is that any Web3 project consists of (1) the ostensible project plus (2) a Ponzi scheme. If you do a thing in a Web3 project, you get some tokens, and then if more people do it the tokens become more valuable; you are rewarded for doing the thing to the extent that new investors put money in after you.”18

Crypto was supposed to provide permissionless crowdfunding with the ability to democratize capital for new projects:

“[O]ne of crypto’s superpowers is the ability to kick-start projects by providing an incentive to get it on the ground floor. The more people who join the project after you, the more money you make.”19 And the more the token appreciates in value, the more people will want to buy and keep it.

“Regulatory arbitrage” is how Ben Thompson of Stratechery described it in 2021:

“[S]cams and Ponzi schemes are everywhere, and it seems clear that we are in the middle of an ever-inflating bubble. It’s also the case that an entire set of legitimate use cases are in reality regulatory arbitrage.”20

So if every crypto/Web3 token that a venture capital firm invests in is both a product and an investment opportunity, it presents a regulatory paradox:

If you are a crypto company, crypto fund or an exchange that lists the tokens, you might say, “no, this is a utility token with consumptive uses, financial speculation is a mere byproduct, and there is no common enterprise or third party efforts because it is sufficiently decentralized, just like Bitcoin. This is not a security.”

But if you are the SEC and ostensibly want to protect investors from potential scams, you might say “Bitcoin is not a security, but everything else on Crypto Twitter looks and feels like scammy investments. Everything is a security!”21

And you might both be right. A crypto token can be both a security and not a security. Crypto is the Schrödinger’s cat experiment of the regulatory world.22

If Everything is a Security, Why Doesn’t the SEC Shut Down the Crypto Industry?

Maybe the SEC is resource-strapped and it doesn’t have enough political capital to shut down the entire U.S. crypto industry.

That’s possible, but the SEC might also be taking a wait-and-see approach. The SEC can regulate in two ways. The first is to make and interpret rules (“Rulemaking”). The other way is to bring enforcement actions (“Enforcement”). The crypto industry would prefer Rulemaking, while the SEC seems to prefer regulation by Enforcement.

The VC industry is largely self-policed and relies on Rulemaking. Rarely does the SEC go after a venture capital firm. That’s the result of clear and consistent rules, a body of SEC no-action letters that apply to real world situations and industry compliance with rule of law, including the accredited investor rules.

The crypto industry is regulated by selective Enforcement. The SEC has not opened up Rulemaking to the crypto industry. So in the absence of fraud or tangible harm to investors, wide-reaching fines and cease-and-desist orders like the Telegram case may be hard to justify.

Conclusion

The regulatory arbitrage that crypto industry enjoyed seems to be coming to an end. It may take a while before the crypto industry adapts. The SEC will likely bring a lot more enforcement actions to get its point across. Is there a better way to regulate? The venture capital industry seems to have it figured out. Maybe we should take note.

Subscribing to the Law of VC newsletter is free and simple. 🙌

If you've already subscribed, thank you so much—I appreciate it! 🙏

As always, if you'd like to drop me a note, you can email me at chris@harveyesq.com, reach me at my law firm’s website or find me on Twitter at @chrisharveyesq.

Thanks,

Chris Harvey

A “security” is defined throughout the relevant securities laws, including in Section 2(a)(1) of the Securities Act of 1933, Section 3(a)(10) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934, Section 2(a)(36) of the Investment Company Act of 1940, and Section 202(a)(18) of the Investment Advisers Act of 1940: “any note, stock, treasury stock, security future, security-based swap, bond, debenture, evidence of indebtedness, certificate of interest or participation in any profit-sharing agreement, collateral-trust certificate, preorganization certificate or subscription, transferable share, investment contract, voting-trust certificate, certificate of deposit for a security, fractional undivided interest in oil, gas, or other mineral rights, any put, call, straddle, option, or privilege on any security, certificate of deposit, or group or index of securities (including any interest therein or based on the value thereof), or any put, call, straddle, option, or privilege entered into on a national securities exchange relating to foreign currency, or, in general, any interest or instrument commonly known as a “security”, or any certificate of interest or participation in, temporary or interim certificate for, receipt for, guarantee of, or warrant or right to subscribe to or purchase, any of the foregoing.”

Public registration is generally not an option if you are venture capital adviser. Only two modern venture funds have ever registered their offerings, including one that just launched on September 27th, 2022 (Cathie Wood’s ARK Venture Fund). Venture capital funds rely on a few key exemptions, including Rule 506(b) and Rule 506(c) of Regulation D.

The SEC estimates the US equity markets has $115 trillion in securities trading annually, with $17 trillion locked in funds and $40 trillion in the U.S. fixed income market. By comparison, the the US housing market is worth $43 trillion, which 2x’d over 10 years. More wealth is captured and traded in the capital markets than is locked in non-securities.

All original ideas and credit goes to Paul Graham’s essay on How People Get Rich (2021). Good artists copy.

(Ed. on 10/1/22 - originally had this statement written as trillions, apologies for the error).

See Reves v. Ernst & Young, 494 U.S. 56, 61 (1990) (“Congress painted with a broad brush. It recognized the virtually limitless scope of human ingenuity, especially in the creation of ‘countless and variable schemes devised by those who seek the use of the money of others on the promise of profits,’ and determined that the best way to achieve its goal of protecting investors was to define the term 'security' in sufficiently broad and general terms so as to include within that definition the many types of instruments that in our commercial world fall within the ordinary concept of a security.”).

See SEC v. W.J. Howey Co., 328 U.S. 293, 298 (1946).

The two core features of an investment contract are profit expectations and the efforts of other people. The last prong of the Howey test originally required expected profits come “solely” from the efforts of others. This was broadened to mean primarily or substantially, and should represent situations where investors have more passive roles than active ones.

But at least one case held that 160 investors in a partnership was not a number so large that each partner’s role was “diluted to the level of a single shareholder.” See Koch v. Hankins, 928 F.2d 1471, 1479 & n.12; see also Rivanna, 840 F.2d at 242 n.10 (4th Cir. 1988).

See United Hous. Found., Inc. v. Forman, 421 U.S. 837, 858 (1975) (describing a security transaction as “an investment where one parts with his money in the hope of receiving profits from the efforts of others, and not where he purchases a commodity for personal consumption or living quarters for personal use.”).

See fn #4, above, Reves, 494 U.S. at 61.

This may not be a 100% accurate reading of Gensler’s stated position, but it is an accurate reading of his revealed position based on the SEC’s most recent enforcement actions.

Jacobellis v. Ohio, 378 U.S. 184, 194 (1964) (Stewart, J. concurring).

Matt Levine, Crypto Regulators Aren’t Very Sympathetic (Sept. 22, 2021).

Matt Levine, Money Stuff: Washing Web3 (Jan. 19, 2022).

Matt Levine, Money Stuff: Web3 and the Ponzi economy (Feb. 7, 2022).

Kevin Roose, Maybe There’s a Use for Crypto After All, The New York Times (Feb. 6, 2022).

Ben Thompson, The Great Bifurcation (Dec. 14, 2021).

Hat tip/all credit goes to Matt Levine for I have truncated his signature phrase, “Everything is Securities Fraud.”

Schrödinger’s Securities: Regulation & The Quantum State Of Crypto, Hackernoon (2018).