#28 Episode - Everyone in VC is an Accredited Investor

Accredited Investor Rules May Be Modernizing, But Will Anything Change for Venture Funds?

Key Takeaways: A new proposed law would create an exam for non-accredited investors to become accredited. But due to venture fund limits and other regulations, the impact may be closer to zero. Three recommendations to fix that: Increase the number of LPs allowed per fund, open up equity crowdfunding to funds, and ease restrictions on qualifying investments in VC funds.

This past week, securities lawyers have been bombarded with breaking news updates. Amid the noise, one interesting headline stood out:

The U.S. House passed a bill with strong bipartisan support (383-18 vote) allowing potential investors to qualify as accredited investors through a test 🎓

Many people thought this was a good idea:

Others weren’t so sure:

One securities lawyer lamented that the bill must still pass Senate approval where:

“It will die, as usual.”1

But even if the legislation was eventually enacted into law, would anything change?

To answer that question, we will start with an understanding of accredited investor laws, review the new law and its potential impact, and make some recommendations.

I. Understanding Accredited Investor Laws

In 1982, the SEC established accredited investor rules to define who is qualified to invest in private securities offerings. Accredited investors are those eligible to invest in unregistered offerings not generally available to the public.

Around 13% of US households qualify as accredited investors, but less than 1% of eligible accredited investors actively invest in US venture capital, while nearly 100% of non-accredited investors are locked out of venture capital funds.2

The SEC has 13 accredited investor categories which can be split into two groups:3

Operators

LPs and Funds

Operators

Operators such as fund managers, knowledgeable employees4 and other industry professionals, automatically qualify as accredited investors, including:

Industry Professionals

Exempt reporting advisers (ERAs) filing with the SEC

SEC- or state-registered investment advisers

Registered broker-dealers

Professionals in good standing with Series 7, 65, or 82 licenses

In 2020, the law was amended to qualify certain operators as accredited investors, including (1) venture capital fund advisers, (2) private fund advisers, and (3) knowledgeable employees, even if they would not otherwise meet the criteria of accredited investors on their own.5

This means that every venture capitalist should be deemed to be an accredited investor of their own fund—regardless of their wealth, income, net worth, or sophistication.6

But what if you’re investing as a limited partner (LP) of a fund—are the rules different?

LPs and Funds

For LPs and funds, the accredited investor rules differ. They must meet certain wealth-based standards instead.

Individuals

The standards for natural persons are based on net worth and income criteria, including:

A net worth of $1+ million (excluding one’s primary residence); or,

An annual income of $200,000 (or joint income of $300,000 for a couple).

Entities

Under this category, corporations, LLCs, limited partnerships, family offices, and trusts must generally have “in excess of”:

$5 million in total assets

A catch-all rule that qualifies entities which have at least:

$5 million in investments

Entities whose equity owners are all accredited investors also qualify as accredited investors

Self-Certification

Section 4(a)(2); Rule 506(b)

What are the securities laws related to accredited investor rules?

Section 4(a)(2): This private placement exemption allows funds to sell LP interests without having to register with or disclose the sale to the SEC.7

To qualify for this statutory exemption, investors must:

Be sophisticated investors;

Have access to the same type of information that would normally be provided in a prospectus for a registered securities offering (PPM); and,

Agree not to sell or distribute the securities to the public.8

Rule 506(b): This exemption allows an unlimited number of accredited investors and an unlimited amount of capital.

To qualify for this safe harbor, the fund must:

Not advertise or generally solicit their offering;

Have a reasonable belief all investors meet the accredited investor rules;

No more than 35 non-accredited investors.9

Regulatory oversight of the venture capital industry is limited. It relies heavily on self-regulation. As a result, LPs often self-certify their own accredited investor status.10

Reasonable Steps to Verify

Rule 506(c)

But there are exceptions. Any fund manager who either (i) publicly advertises their offering or (ii) generally solicits LPs without a substantive, pre-existing relationship must take “reasonable steps to verify” each LP is an accredited investor.11

Under this rule, self-certification is not enough. Acceptable methods include:

Income: IRS tax documents along with investor’s representations;

Net Worth: Bank statements (or similar reports) with investor’s representations;

Third-Party Verification: A third-party verification letter from the investor’s financial adviser, attorney or CPA issued within the last 3 months;

Re-Verification: If a person has been previously verified as an accredited investor, the issuer can reconfirm their status via self-certification, valid for up to 5 years.

The SEC takes a “principles-based approach” to verifying accredited investor status, which means that the methods listed above are not the only ways to take reasonable steps.12

Venture funds are frequently relying on third-party software platforms for this. But is it possible for a conflict of interest to arise when a venture-backed platform, which stands to gain from new investors, is also in charge of confirming investors’ statuses? Might this be a situation that casts doubt on whether these platforms can actually take “reasonable steps” to filter out non-accredited folks? Maybe, but who cares?13

II. Reviewing The Exam

Let’s review what the Equal Opportunity for All Investors Act of 2023 provides.

It would create an exam-based certification process for non-accredited investors to become accredited investors, free of charge.

As accredited investor laws are primarily based on wealth and income thresholds, this would open new regulatory pathway for non-traditional investors to participate in private securities offerings.

The exam would have to be designed by the SEC within one year and administered by FINRA to ensure it has an appropriate level of difficulty such that an individual with financial sophistication would be unlikely to fail it.

Key Topics to be Covered?

Different types of securities

Private and public company disclosure requirements

Corporate governance

Understanding financial statements

Identifying potential conflicts

Aspects of unregistered securities, including risks associated with limited liquidity and disclosures, among other potential pitfalls

Importantly, the exam will not require an annual license, unlike the current accredited investor rules which require a “license in good standing” after passing one of the Series 7, Series 65 or Series 82 exams.14

III. Impact on the VC Landscape

For argument’s sake, let’s assume the Equal Opportunity for All Investors Act is enacted into law. The likely outcome is that without further regulatory changes, it won’t have any impact in terms of new accredited investor participation in funds.

How many limited partners invest in US venture funds currently?

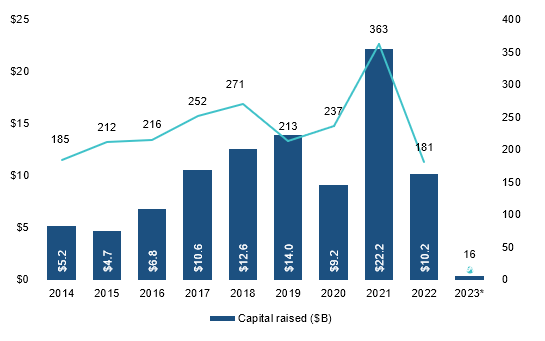

According to the NVCA-PitchBook 2023 Yearbook, as of 2022, there are 3,756 active VC investors with assets under management of approximately $1.2 trillion, including $330 billion in dry powder.15

AngelList says it has more than 2,225 active fund managers with approximately 15,000 venture capital funds listed on their Form ADV in 2023.16 Most of these funds are solo GPs and it would be hard to estimate how many LPs are in each fund.

But if we know the industry’s average number of limited partners per fund, we can estimate the total number of limited partners across the ecosystem. According to the SEC, between 2009 and 2019, the average number of investors per VC fund was 15. There was a spike in VC fundraising activity between 2020-2022, which roughly doubled the size of funds in those two years, but has since come down 90% or more.17

Estimated number of active venture capital funds in the US:

4,000 funds to 6,000 funds

Estimated average number of LPs per fund:

15-20 LPs

Total Number of LPs investing in venture in the US:

Lower bound: 60,000 LP positions

Upper bound: 120,000 LP positions

But if we assume that the average LP invests in more than one fund (call it an average of two), we can adjust our initial estimates to account for duplicates:

Let’s do this for the lower and upper bounds:

Lower bound: 60,000 LP positions / 2 = 30,000 unique LPs

Upper bound: 120,000 LP positions / 2 = 60,000 unique LPs

These are just estimates, but the actual numbers are probably far lower.

What about the number of limited partners allowed per venture capital fund?

One of the main reasons the house bill will have little impact on venture capital funds is because of the limitations set by the Investment Company Act of 1940 (ICA).

Section 3(c)(1). Funds with any accredited investors are limited to accept only 100 persons (or 250 persons for venture funds less than $10 million).

That means for a $10 million fund, with 250 available LP slots, the average LP commitment must be $40,000.

That means for a $50 million fund, with 100 available LP slots, the average LP commitment must be $500,000.

Again, these are hypothetical LP minimums.

The data indicates the average minimum LP commitments rose between 2018 and 2020 from ~$400,000 to $1.43 million, and the median 2x’d from $250,000 to $500,000.

Even though these are “capital commitments”—which means they will be spread over years with multiple capital calls—non-accredited investors generally have fewer resources to invest. And these LP minimums are high even for people with the means to invest, making it difficult to attract enough newly minted accredited investors to reach the VC fund’s target fund size. Additionally, managing a large number of smaller LPs can be administratively burdensome and increase costs for venture funds.

Even if Congress opens up the doors to non-accredited investors, the math does not make sense for them to participate in venture funds as they are currently regulated.

IV. Recommendations

Despite these challenges, there is a interest in democratizing venture capital and expanding the pool of potential investors who can participate as LPs in venture capital funds.

Emerging regulations like equity crowdfunding and technology-focused venture platforms make it easier for smaller investment amounts, which could gradually make venture investing more accessible to non-accredited investors and emerging LPs.

Here are three sensible legislative recommendations:

1. Increase the Number of LPs Allowed Per Fund

Venture funds are currently limited to accepting 100-250 investors under the SEC rules. Increasing this limit, even modestly, could open up more opportunities for more investors to participate as LPs.

For example, the policy team at the National Venture Capital Association (“NVCA”) and fund managers are speaking up to Congress about increasing the LP limits of venture funds under $150 million from 250 to 600 persons and larger venture capital funds from 100 to 200 persons.18

On February 8, 2023, VC Mac Conwell spoke at a Congressional hearing about this:19

2. Open up Equity Crowdfunding to Funds

Equity crowdfunding allows non-accredited investors to invest in startups, but current regulations (such as Regulation A and Regulation Crowdfunding) explicitly prohibit venture funds from raising capital through crowdfunding portals. Allowing venture funds to crowdfund, even partially, could help them attract more small investors who want to invest $500-$50,000, for example. Venture funds would still be subject to the 100-250 maximum investor limit, but equity crowdfunding could count as one limited partner through a special purpose vehicle used to invest directly into the fund.

3. Ease Restrictions on “Qualifying Investments” in VC Funds

Under current SEC rules, to qualify as a “venture capital fund,” at least 80% of a fund's investments must be in “qualifying investments”:

Qualifying investments are defined as direct issuances of equity and equity-like instruments from startups. Common examples are SAFEs and preferred stock. Under current rules most secondary purchases and fund-of-funds do not count as “qualifying investments”.

However, secondary purchases and fund-of-funds have become increasingly common and important ways for venture capital industry to grow. They allow capital to flow in and out more efficiently, allowing new investors to participate indirectly, and startup companies to exit earlier.

The NVCA has expended significant resources to advocate to fix this:

In short, the DEAL Act would effectively categorize fund-of-fund investments into VC funds and secondary investments as “qualifying investments.” That would allow fund-of-funds to qualify as VC funds, which would reduce their regulatory burdens and allow more beneficial ownership in VC funds.20

So, in summary, these kinds of practical reforms may be realistic pathways toward democratizing venture capital and opening it up to non-traditional investors.

Despite broad bipartisan support in the House, the bill currently has only a 3% chance of passing the Senate, as published on GovTrack (quoting Skopos Labs).

SEC data shows venture funds accepted 0% of limited partners as non-accredited investors. In contrast, the SEC found that between 2009 and 2019, between 3.4% and 6.9% of offerings conducted under Rule 506(b) included non-accredited investors. See Law of VC #11:

The definition of an accredited investor includes the following 13 categories: (Rules 501(a)(1) through 501(a)(13), cited as 17 CFR § 230.501, et seq.)

Rule 501(a)(1): Any venture capital fund adviser or private fund adviser (ERAs), registered investment advisers (RIAs), broker-dealers, and banks.

Rule 501(a)(2): An employee benefit plan if the plan has more than $5 million in assets.

Rule 501(a)(3): Corporations, partnerships, limited liability companies (LLCs), or similar entities, not formed for the specific purpose of acquiring the securities offered, with total assets in excess of $5 million.

Rule 501(a)(4): Any director, executive officer, or general partner of the issuer of the securities being offered or sold.

Rule 501(a)(5): A natural person whose individual net worth, or joint net worth with their partner, exceeds $1 million at the time of the purchase, excluding the value of the primary residence of such person.

Rule 501(a)(6): A natural person with income in excess of $200,000 in each of the two most recent years or joint income with their partner exceeding $300,000 for those years and a reasonable expectation of the same income level in the current year.

Rule 501(a)(7): A trust with assets in excess of $5 million, not formed only to acquire the securities offered, with a sophisticated person making the purchase. Includes a revocable trust in which all the grantors are accredited investors.

Rule 501(a)(8): An entity in which all the equity owners are accredited investors.

Rule 501(a)(9): Any entity owning “investments” in excess of $5 million and such entity is not formed for the specific purpose of acquiring the securities being offered.

Rule 501(a)(10): Professional license holders that pass an exam and are in good standing with one or more professional organizations the SEC has designated as qualifying an individual for accredited investor status. Series 7, 65, and 82 licenses.

Rule 501(a)(11): Knowledgeable employees. See footnote #4, below.

Rule 501(a)(12): Family offices managing in excess of $5 million

Rule 501(a)(13): Family clients of a family office

See Rule 501(a)(11); Law of VC #27: Essential Checklists to VC Fund Formation (FN10):

Under Rule 3c-5 of the Investment Company Act of 1940, a “knowledgeable employee” is generally defined as follows:

Executive Officers and Decision-Makers: Anyone who holds a leadership position in the firm such as an executive officer, director, trustee, general partner, advisory board member, or person serving in a similar capacity within the private fund or an affiliated management company. These individuals generally have decision-making authority and are involved in directing the fund’s investment activities.

Experienced Employees: This category includes employees of the private fund or an affiliated management company who participate in the fund’s investment activities as part of their regular job responsibilities, but does not include employees who only perform clerical, secretarial, or administrative functions. To qualify, the employee must be engaged in the fund’s investment activities or those of other private funds or investment companies managed by the same affiliated entity. Furthermore, the employee must have been performing such investment-related functions for the private fund, its affiliated management company, or a similar fund for at least 12 months.

These “knowledgeable employees” are considered to be accredited investors for the purposes of investing in the funds managed by their employer, as they are presumed to have the knowledge and expertise to evaluate the risks and merits of the investment.

In the SEC’s final rule on “Accredited Investor Definition” the Staff provided the following:

The final amendments to the accredited investor definition will allow knowledgeable employees of private funds to qualify as accredited investors for purposes of investing in offerings by these funds without the funds themselves losing accredited investor status when the funds have assets of $5 million or less.FN359

FN359: Under Rule 501(a)(8), a private fund with assets of $5 million or less may qualify as an accredited investor if all of the fund's equity owners are accredited investors.

There were a few key amendments to Rule 501(a), including Rule 501(a)(1):

§501(a) Accredited Investors. Accredited investor shall mean any person who comes within any of the following categories, or who the issuer reasonably believes comes within any of the following categories, at the time of the sale of the securities to that person:

(1) … any investment adviser relying on the exemption from registering with the Commission under section 203(l) or (m) of the Investment Advisers Act of 1940.

To clarify, “section 203(l) or [§203](m)” refers to “venture capital funds” and “private funds” advisers, respectively.

Technically, Rule 501(a)(1) is limited to venture capital fund advisers and private fund advisers who rely on section 203(l) or 203(m) of the IAA and make SEC filings. (Footnote #5) But GPs and fund managers already qualify as accredited investors of their own fund under Rule 501(a)(11), which is for “Knowledgeable Employees”. (Footnote #4)

Blue Sky filings must be completed in the state where the limited partner resides, and state law will control. Section 4(a)(2) of the Securities Act. In addition, any public advertising of the offering or general solicitation of investors is incompatible with the private placement exemption. There are no explicit limitations but as the number of LPs increases and their relationship with the fund manager becomes more distant, it becomes harder to show that the offering qualifies for this exemption. One misstep blows the exemption.

A “sophisticated investor” is one who either (1) has sufficient knowledge and experience in financial and business matters to evaluate the merits and risks of an investment, or (2) is capable of bearing any loss associated with the investment.

If non-accredited investors are participating in the offering, the company conducting the offering: (i) must give any non-accredited investors disclosure documents that generally contain the same type of information as provided in Regulation A offerings (PPM); (ii) must give any non-accredited investors financial statements; and (iii) should be available to answer questions from prospective purchasers who are non-accredited investors.

Is there a penalty for misrepresenting one’s self-certified accredited investor status? There may be, but I can’t find a single case or action against an investor. Rather, the burden is on the fund—in which case, the standard is “a reasonable belief[]”. See Law of VC #5:

@bryce: Serious question: has anyone been prosecuted for investing in a startup as an unaccredited investor?

@skupor: Unlikely, but as a practical matter since no issuer would take that risk, nor would any law firm issue an opinion signing off on this (which also means that other accredited/qualified investors would not close on the deal), unaccredited investors simply have no access.

Rule 506(c) provides a non-exclusive list of verification methods that are deemed to satisfy the reasonable steps requirement, including reviewing tax forms or other financial documents, obtaining third-party verification letters from certain professionals, or obtaining a written representation from an investor’s professional relationship with verifications must be done within three months. Issuers can rely on written representations for investors they had previously verified within the past five years, as long as they have no information to the contrary.

SEC Final Rule: Eliminating the Prohibition Against General Solicitation and General Advertising in Rule 506 and Rule 144A Offerings, Release No. 33-9415 (“Under Rule 506(c), issuers are required to take reasonable steps to verify the accredited investor status of purchasers. The determination of whether the steps taken are "reasonable" will be objective and based on the particular facts and circumstances of each purchaser and transaction. When conducting this analysis, issuers should consider the following factors: (i) The nature of the purchaser and the type of accredited investor they claim to be; (ii) The amount and type of information the issuer has about the purchaser; and (iii) The nature of the offering, including how the purchaser was solicited to participate and the terms of the offering, such as a minimum investment amount.”)

Regulators may be concerned if securities rules are being skirted, but the SEC does not appear to be prioritizing this particular issue as an area of concern as it does not show up on the SEC’s annual enforcement priorities reports. However, an SEC-authorized report found between 2014-2015, nearly 40% of their enforcement actions involved soliciting vulnerable people, such as the elderly, unemployed, and affinity-based groups. When considering non-accredited investors who were solicited in pump and dump schemes, this figure jumps to over 50%. This suggests a strong correlation between non-accredited investors and SEC enforcement actions. Gullapalli, R. (August 2020). Misconduct and Fraud in Unregistered Offerings: An Empirical Analysis of Select SEC Enforcement Actions. Division of Economic and Risk Analysis (DERA), U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission.

See Rule 501(a)(10); Amendments to Accredited Investor Definition, SEC (Mar. 29, 2021).

See NVCA-Pitchbook Yearbook Report (2023), p. 47.

See NVCA Venture Monitor (2023), p. 4.

By default, under section 3(c)(1)(A), one entity is equal to one beneficial owner, unless it is formed specifically formed to invest in a particular fund. But in the case of fund-of-funds, because they pool their investments across funds, they do not trigger that look-through rule.

Question from a European focused dude here. So, am I right in reading that an operator (i.e. VC) owned entity is deemed an accreditor investor if investing as an LP into a US fund?